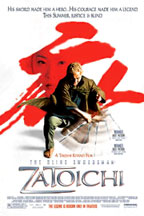

ZAOTOCIHI -2004

Director: Takeshi Kitano

Writer: Takeshi Kitano

Producers: Masayuki Mori/Tsunehisa

Cinematographer: Katsumi Yanagijima

Editor: Takeshi Kitano

Music: Keiichi Suzuki

Running Time :111

Rating : R

Cast: Takeshi Kitano Beat Takeshi (Zatoichi), Tadanobu Asano (Gennosuke Hattori), Yui Natsukawa (O-Shino), Michiyo Ookusu (Aunt O-Ume), Gadarukanaru Taka (Shinkichi), Daigorô Tachibana (Geisha O-Sei), Yuuko Daike (Geisha O-Kinu), Ittoku Kishibe (Ginzo), Saburo Ishikura (Boss Ogi)

Zaotoichi is a bloody film that also manages to be beautiful and funny, most critics tend to describe Takeshi Kitano's eleventh film as something of a departure for the filmmaker. Takeshi Kitano, best known for such gangster films as VIOLENT COP, BOILING POINT, and BROTHER, makes his first period drama, an updating of the classic Japanese I suppose, in a way, it is-most western audiences seem to only be familiar with Kitano's stoically violent yakuza (Japanese gangster) movies and not with some of the more traditional films in his oeuvre (the serene A Scene at the Sea, the offbeat comedy Getting Any? or the haunting Dolls for example). Taking that into consideration, and the director's penchant for writing, directing, editing, and starring in his own productions, seeing Kitano tackle a Japanese icon like Zatoichi in a "hired gun" fashion is certainly a bit of a step into a new arena.

Zatoichi is one of Japanese cinema's most enduring characters, a blind masseuse who was also a master swordsman. Katsu Shintaro starred as the character in all twenty plus films made during the span of two decades and even appeared several different television spin-offs. The Zatoichi films featured typical samurai cinema fare mixed in with some light comedy elements (often at the title character's expense). One critic has made the comparison that Zatoichi is to Japan what James Bond is to the west. In terms of instant recognition to its respective audience, that's probably true.

Zatoichi certainly breaks from a few of the traditions of the earlier films (the hair, the bright red cane-sword, etc.), it always remains respectful of the much loved earlier entries. What's most interesting about Zatoichi isn't how the film sticks to or breaks from the traditions of the countless Katsu Shintaro vehicles, but instead in how it breaks from and sticks to the well-publicized conventions of Kitano's cinema. It doesn't seem like a particularly drastic departure in retrospect (given that the filmmaker's next three films after this one-Takeshis, Glory to the Filmmaker, and Achilles and the Tortoise-would be self-referential postmodernist meta-films that asked for a great deal of patience from their audience), but at the time, it was the first sign that the winds of change were blowing in the auteur's perception of his work.

Narratively, the film is simple and very much like the classic Zatoichi films. Ichi wanders into town and soon finds himself embroiled in a quest for revenge undertaken by two geisha (one a transvestite) whose parents were murdered by the local yakuza years earlier. Like the originals, Kitano's film features more story than action-Ichi certainly gets his moments to shine (as does his nemesis, a ronin bodyguard played by Tadanobu Asano). Unlike the originals, it also boasts several musical numbers (including an ensemble tap dancing sequence) and a lot more blood and body parts.

Kitano's films have always been known for their violence, and Zatoichi is no exception-limbs fly and blood squirts every time a blade is unsheathed. What makes this film so different, though, is that unlike earlier films in the director's body of work, Zatoichi presents a very stylish kind of violence. Scenes in films like Fireworks and Sonatine are memorable for their brutal (yet realistic) depictions of death and destruction. Kitano's carnage in those films is never glamorous or particularly stylized. It's the antithesis of Hong Kong action cinema from the same period, which made every shootout a ten minute long spectacle complete with people flying through the air while firing guns from each fist. Zatoichi never reaches (or even comes close) to the stylistic excesses of Hong Kong cinema, but it does mark a departure from Kitano's norm (as do the countless short shots, abbreviated takes, and scenes using cranes and dollies-this really is a whole new Kitano in some ways).

Generally speaking, this new view of violence is satisfying. The only thing that mars the film's various swordfights is an artistic decision to utilize CG for the wounds and blood. Kitano has explained this decision as a stylistic one, designed to give the film the feel of a videogame. It succeeds in that regard, but it tends to pull the audience out of the action. It looks off and stands in stark contrast to the filmmaker's crisp visuals and elaborately conceived fight choreography.

This newfound fascination with choreography colors not only the fight scenes (which serve as perfect visual descriptors of each of the two main characters-Asano's fights are the overly staged battles of countless chanbara films, while Kitano's are more Iaido driven and grounded in reality) but turn up in the film's musical numbers as well. You read that right-Takeshi Kitano has managed to work several musical interludes into a samurai film. The most elaborate comes at the end when the good guy characters team up with scores of other locals to tap dance us into the credits. The scariest thing about this sequence is how well it works. Kitano subtly prepares us for it earlier in the film, choreographing fieldworkers to the soundtrack, then raindrops, and even carpenters building a house. By the time he cuts loose with the full on dance number at the end, it seems less out of place and more like something that's grown from the seeds he planted earlier in the film.

The only real disappointment with Zatoichi is that I found the musical score rather underwhelming. Kitano spent most of his career working with composer Joe Hisaishi and their collaborations are some of my all time favorite pieces of film music. The duo had some sort of falling out after Dolls and haven't worked together since. Hisaishi's classical piano scores would have worked quite beautifully with the action sequences, I think, but instead Kitano chose to go with Keiichi Suzuki. Suzuki's compositions aren't terrible-they're just not what I expect from a Kitano film after so many classic Hisaishi soundtracks over the years.

Minor disappointments aside, Takeshi Kitano's Zatoichi is an excellent film from one of the greatest filmmakers working today. It may not be an entirely Kitano production, but the director has still managed to place his own unique directorial stamp on the project, all while foreshadowing the complete change of direction that was about to appear in his next three films. Comparing Kitano's Zatoichi to Katsu Shintaro's is both pointless and unfair. No one will ever make a Zatoichi film like the Katsu ones-and Kitano understands that and tries to pay his respects while doing his own thing. The end result is a film that succeeds in pleasing both longtime fans of Zatoichi and the admirers of Kitano's more traditional work.